From Detention to Diagnosis: Understanding My ADHD

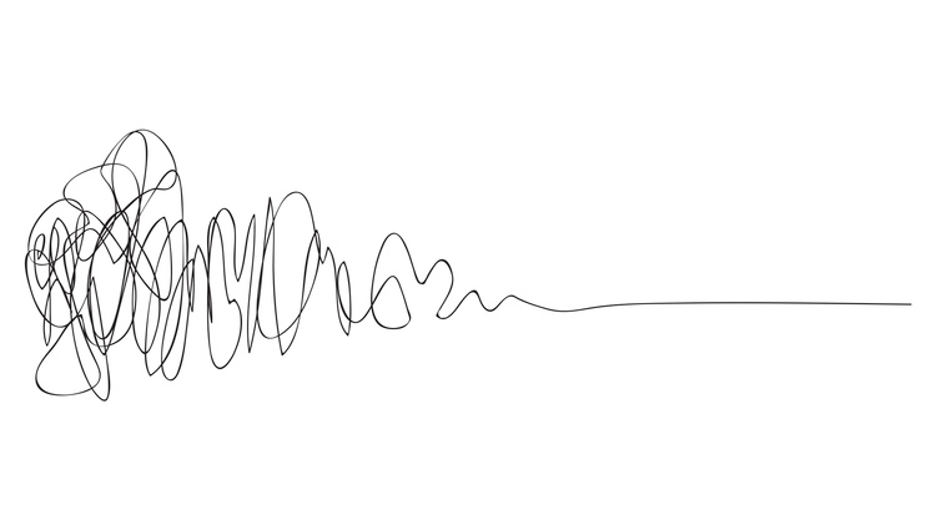

The image above is Damien Newman's 'Design Squiggle', which visualises the creative process: it starts chaotic and uncertain during research and exploration, then gradually becomes clearer as patterns emerge and concepts are tested. By the end, the tangled line straightens into a focused solution. It illustrates that messiness isn't failure, but a necessary path from complexity to clarity - a fitting metaphor for my journey with ADHD.

I recently came across Alina Vandenberghe's post about her experience with what she describes as likely autism, and something in her brave and candid words struck a deep chord and inspired me to be a little braver and share a similar story.

The Record-Breaking "Bad Kid"

I wasn't a troublemaker in the way you might expect. I never did anything immoral or deliberately harmful. I was just... distracted. Endlessly, relentlessly distracted. My mind was always somewhere else, chasing a thought, noticing a pattern, making connections that had nothing to do with the maths problem in front of me.

The school system didn't know what to do with that version of me, so they punished it. Detention after detention after detention. I racked up what must have been a record-setting number of hours. And somewhere along the way, those detentions crystallised into an identity: I was the "bad kid." Not the distracted kid. Not the kid whose brain worked differently. Just bad.

That label stuck. It followed me through corridors, into new classes, into the assumptions people made about me before I even opened my mouth. When you're repeatedly told you're bad for things you can't seem to control, you start to believe it.

The Intelligence Paradox

Here's what made it even more confusing: I always felt intelligent. I could make connections others missed. I could see patterns, think creatively, solve problems in unconventional ways. But my school results told a different story.

ADHD typically manifests noticeably in males during the early teenage years, right when the curriculum steps up and study becomes non-negotiable. Suddenly, it wasn't enough to just absorb information in class. You had to sit still, focus on command, and revise material that might not interest you at all.

For me, study was torture. My brain simply refused to engage with material I found boring, no matter how important it was supposed to be. I'd sit at my desk, open my textbooks, and within minutes, my mind would be anywhere but on the page in front of me.

But here's the thing: when something did interest me, I couldn't stop. I'd dive so deep into a topic that I'd emerge hours later, having forgotten to eat, forgotten the time, forgotten everything except the fascinating rabbit hole I'd fallen down. This wasn't a lack of focus. It was an inability to control where my focus went.

The Superpowers They Don't Talk About

Like Alina, I've discovered that many of these traits that made life difficult have another side to them. The extreme social awareness is real. I can walk into a room and instantly feel the energy, read the micro-expressions, sense the unspoken tensions or connections. In commercial settings or important meetings, this is invaluable.

That sensitivity to stimuli that made school environments overwhelming? It also means I notice details others miss. The quick thinking under pressure that comes from a brain that's always making unexpected connections? That's helped me navigate countless challenging situations.

I resonate deeply with Alina's observation about needing "quiet after noise" and "thinking in spirals instead of straight lines." The world is built for linear thinkers, for people who can follow a straight path from A to B. But sometimes the most interesting insights come from spiral thinking, from making connections across seemingly unrelated domains.

The Five-Minute Diagnosis

I didn't set out to get an ADHD diagnosis. I went to see a counsellor because of depression, expecting to talk about low moods and stress. Within the first five minutes of our conversation, he said something that stopped me in my tracks: "I'm going to work on the basis that you have ADHD."

I had no idea what I'd said or done to prompt such a quick assessment. Looking back, I imagine it was the way I spoke, the tangents I went on, the patterns in how I described my experiences. Whatever he saw, he saw it immediately.

Getting that diagnosis didn't just give me a label. It gave me a completely different lens through which to view my entire life. Suddenly, all those detentions made sense. The academic struggles despite feeling intelligent made sense. The ability to hyperfocus on some things while being unable to engage with others made sense.

I wasn't bad. I wasn't lazy. I wasn't lacking in discipline or moral character. My brain was just wired differently, and nobody, including me, had understood that.

The Mourning Period

What I didn't expect was the grief. Not overwhelming, but real nonetheless. I went through a short mourning process for "what could have been." What if I'd had medication to help me focus? What if teachers had understood? How might my relationships have been different? My education? My early career?

These weren't productive questions, but they needed to be asked. They needed to be felt. Because part of accepting who you are now means acknowledging what you went through to get here.

But here's what I've come to understand: I can't change the past, but I can change how I move forward. The diagnosis didn't erase the years of being labelled the "bad kid," but it did allow me to rewrite that narrative. I can now look back at my younger self with compassion instead of shame. That kid wasn't broken or bad. He was just trying to navigate a world that wasn't built for the way his mind worked.

Working With, Not Against

I'm glad I finally looked into this. Understanding how I operate, and more importantly, not fighting against it anymore, has been transformative. It's helped with work, with my marriage, as a father. I'm not trying to force myself into a neurotypical mould anymore.

The fundamentals matter more than I ever realised: prioritising sleep and exercise has been crucial. An ADHD brain needs these foundations even more than a neurotypical one.

At work, I've learned to accept that I experience highs and lows deeply. Some days I'm firing on all cylinders, making connections others miss, solving problems creatively. Other days are harder. What's helped is maintaining a longer-term view of incremental growth and improvement, both with Gondola and with myself. Progress isn't linear, and that's okay. My brain doesn't work linearly anyway.

I've stopped beating myself up for the things my brain struggles with and started leaning into the things it does well. That shift in perspective changes everything.

Self-Awareness as a Leadership Tool

One of the most important things I've learned is recognising my own state, particularly in a work environment. As a busy founder, husband, and father of three boys, tiredness is inevitable. But being tired with ADHD isn't just about feeling sleepy. It affects mood regulation, increases introversion, and makes it harder to show up as the leader and colleague I want to be.

Building relationships and trust takes time and consistency. It's hard-won and easily damaged. I've learned that I need to have strategies and tools in my toolkit for those challenging days, including medication when needed. This isn't about masking who I am or being someone I'm not. It's about treating ADHD as the legitimate medical condition it is, so I can show up authentically and effectively.

There's still stigma around ADHD treatment, particularly in leadership contexts. But I'd rather be honest about having tools that help me regulate my mood, stay calm, and be present for my team than pretend I can white-knuckle my way through every difficult day. Self-awareness isn't a weakness. Knowing when you need support and actually seeking it is a strength.

The goal isn't perfection. It's consistency in moving positively forward, both for myself and for the people who depend on me.

Breaking the Cycle: What I Hope for My Sons

Perhaps the most important impact of understanding my ADHD has been in how I approach fatherhood. I have three boys, and I watch them carefully, not to catch them doing something wrong, but to understand how each of their minds works.

They're each unique. They function differently. They learn differently. And that's not just okay, it's something to celebrate and work with, not against.

My wife Ruby has been on this journey with me, through the depression that led to the diagnosis, through the mourning period, through learning how to work with rather than against my ADHD. It hasn't always been easy for her, helping me navigate the lows, understanding the patterns, adapting to how my brain works. But we're so much better for it now.

We're grateful for those hard life experiences. They've taught us things that we can now use to help our children. We understand that struggling doesn't mean failing. We know that different minds need different approaches. We've learned patience and compassion through our own challenges, and that makes us better equipped to offer those things to our boys.

I'm grateful that we're living in a time of greater acceptance around neurodiversity. We understand now that differences in how brains work aren't defects to be corrected, but variations to be understood and accommodated. We can shape learning and activities to suit those differences, rather than forcing every child through the same rigid system and labelling the ones who struggle as "problems."

When I see one of my boys getting distracted, I don't see a discipline issue. I see a mind that might work like mine. When I see intense focus on something they love and resistance to things that bore them, I recognise that pattern. And instead of punishment, I can offer understanding and strategies that actually help.

I can't change what happened to me in those detention rooms, but I can make sure my boys never internalise the message that being different makes them bad. They'll know their brains might work differently, and that's not just acceptable, it can be a strength. They'll understand themselves earlier than I understood myself, and that understanding might save them years of shame and confusion.

That's worth everything.

The world needs different kinds of minds. It needs people who think in spirals, who feel deeply, who can read a room and sense what others overlook. It needs people who can hyperfocus when they're passionate and who bring unconventional perspectives to conventional problems.

If you're reading this and seeing yourself in these experiences, know that you're not alone. And you're certainly not "bad." You're just different. And different, as it turns out, can be pretty valuable.

What's your experience with ADHD or neurodiversity? I'm always happy to speak about this and I'd love to hear your story, so feel free to send me a message if you'd like to chat.